The School Choice Revolution Will Not Be Televised

Unbeknownst to many, the 'One, Big, Beautiful Bill' could supercharge school choice efforts nationwide

Just a reminder that the 1979 NBA Championship does NOT belong to the Oklahoma City Thunder, despite what Adam Silver’s squad of historical revisionists will tell you. Anyhow, if it’s Friday, it’s Family Matters.

Easy as 1-2-3, Simple as Do-Re-Mi: A “big, beautiful” school choice provision

Like a Rolling Stone: New IFS report on child benefits

It’s Me, Hi: Vox, The Dispatch

Parting Shots

Easy as 1-2-3, Simple as Do-Re-Mi

When you legislate via omnibus, lots of things fly under the radar. And while Family Matters will continue to praise and criticize various high-profile pieces of the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act,” a provision relating to education hasn’t gotten much attention. Yet, if it the bill passes in something close to its current form, it may very well end up the legislation’s longest-lasting legacy.

As of May 2025, there are currently fifteen states that offer no school choice options to families; 35 percent of children age 3-17 live in a state that offers no form of assistance if they choose a private school option. If President Trump signs the legislation in something close to its current form, the roughly 22 million kids who live in a state without school choice would, for the first time, have at least some access to avenues to help them find the school that best fits their child’s needs and their family’s values. In its current form, the Republican legislation would create, essentially, one big, beautiful federal school choice program.

The original idea stems from a 2019 bill introduced by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), who has been one of the most energetic leaders on the school choice front in D.C.1 In its current iteration, it would allow donors to collect a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for donations made to an eligible scholarship-granting organization. (The tax credit would be capped at 10 percent of a taxpayers' adjusted gross income, with a total of $5 billion in federal tax expenditures annually.) Families making less than 300 percent of their area’s median income would be eligible for these scholarships.

To put this in concrete terms – if a taxpayer decided to write a $6,760 check (the average tuition charged by a Catholic school) to an organization that pays for private school tuition, that taxpayer would then be able to get a $6,760 credit on their tax return.2 The credit can even be carried forward, if the amount of their donation exceeded that year’s tax liability. And, as a result, a family who had been prohibited from considering private school because of the cost would have a new vehicle to make that a reality.

This would bring the ongoing school choice revolution to the federal level. In 1997, Arizona became the first state to offer this kind of tax-credit scholarship, and after the Supreme Court ruled the approach constitutional in 2011, it started to spread. According to the school choice advocacy organization EdChoice, the model has since spread to a total of 18 states, with the largest number of student participants found in Pennsylvania.

While the Left generally opposes any school choice legislation, this inclusion is notable for originally having been criticized from the right. When Cruz introduced the original legislation, the Heritage Foundation’s Lindsey Burke and Adam Michel opposed the idea, on the grounds that “a federal tax-credit scholarship program poses a threat to education choice in the states, and undermines the goal of a streamlined federal tax code.” They were worried about creating the precedent for federal strings on a national school choice program, and favoring a narrow tax credit provision over the longtime libertarian-favored policy of lowering tax rates across the board (this bill, of course, tries to do both.)

When he was at National Review, Robert VerBruggen had a separate bone to pick with the idea of tax-credit scholarships. If a state wants to pass vouchers, it should, VerBruggen repeatedly argued, but:

“If the public isn’t willing to allocate its tax money to vouchers, voucher supporters such as [Cato’s Andrew] Coulson and I should work harder to convince them — and not rely on tricks such as tax-credit voucher programs, which, in my view, essentially allow politicians to rebrand government-funded voucher programs as “donations” by private entities, making them easier to pass.”

On the level of principle, VerBruggen’s objection is sound. Giving politicians a back door to claim politically-desired spending isn’t really government dollars could open the door to all sorts of shenanigans. (“No, we’re not funding Planned Parenthood,” a blue state could conceivably say. “We’re just reimbursing rich donors who want to fund Planned Parenthood via a dollar-for-dollar income tax credit.”) And there’s no denying that the structure of the credit is allowing the wealthy to lower their tax burden, even if it is in exchange for providing a private school scholarship.

But in the real world, tax-credit scholarships have shown themselves to be fairly popular, politically durable, and responsible for, per EdChoice, over 217,000 scholarships nationwide. While the dream of lowering rates and closing loopholes came to pass in 2017’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, both parties are now merrily embarking on once again legislating through the tax code, as both the respective progressive and conservative iterations of “BBB” indicate. And given that the school choice train has left the station in red states, Republican lawmakers know that likely the only viable way of extending similar opportunities to kids in blue states is at the federal level.

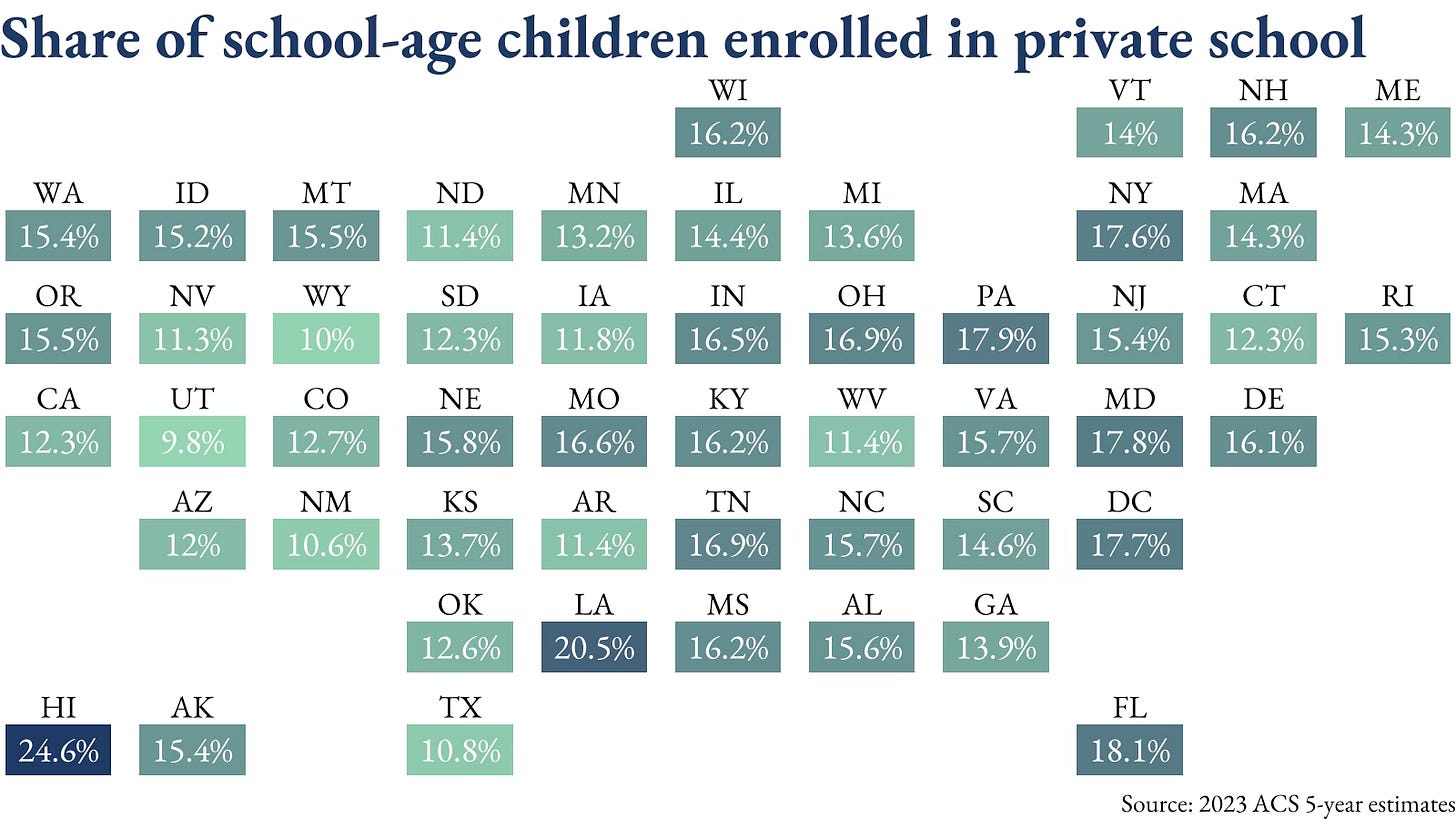

Conventionally, private school enrollment has been as much a function of income as politics, such that wealthy blue states on the East Coast tended to have higher rates of private school enrollment than staunchly red ones like Utah or Texas. As of 2023, the average share of students age 3-17 attending private school in states that would vote for Trump or Harris was almost exactly even, with red state families just slightly more likely to attend private school than the national average.

But that will continue to shift as more and more red states make school choice programs available. A federal approach may be the only way of helping families in Naperville, Bakersfield, Utica, or Walla Walla afford to send their child to a parochial school. Plus, as Chalkbeat’s Erica Meltzer points out, school choice programs often poll well among black and Latino voters. (Though, as my EPPC colleague Stanley Kurtz never fails to note, the majority of students will continue to attend public schools, necessitating that Republicans not ignore the work of improving them.) And some states that have limited school choice programs now could see more options for families in the wake of this legislation. So slipping Sen. Cruz’s tax credit legislation into the package may meaningfully deliver for households that otherwise wouldn’t see much reason to root for passage.3

Due to the exigencies of budget scoring and their other various priorities, the credit is allocated just for the years 2026 through 2029, meaning that a future Congress would need to set aside money to keep it going after that. Yet it’s more likely that universal school choice would develop a constituency to advocate for its continuation after four years than, say, “Trump Accounts,” whose benefits wouldn’t be felt by beneficiaries for at least fourteen more years.

Republicans’ signature reconciliation legislation crams as many political priorities into one package as possible, hoping that offering something for everything will cover the bill’s many flaws. Whether they can fix the various parts of the bill — a bill, let one be reminded, that as drafted currently adds nearly $4 trillion to the federal deficit while both cutting taxes in a way that most advantages higher earners and also cutting safety-net benefits for low-income Americans — while keeping all the various factions in the caucus on-side is very much an open question.

But if some version of the bill makes it across the finish line — which, as a matter of political reality, it must — it seems likely to include one of the most significant expansions of school choice in the nation’s history. Indeed, the best reports as of today are that the Senate is more likely than not to pass something close to the House version of the bill than to push for major changes that could upset the apple cart. Which leaves some conservatives doing a bit of an awkward dance.

There are some who might wince at the impact of the bill on our federal deficit (like me), worry about the impact of cutting aid for low-income families (like me), grimace at some of its less-defensible provisions (hi), or wish the package had been designed to be more generous to parents rather than various political constituencies, like seniors or blue state homeowners (me again). But they will not be able to gainsay the policy victories that would be accomplished via its passage, from defunding Planned Parenthood, to barring Medicaid funds going for gender-reassignment surgeries, and enacting an unprecedented federal school choice program.

The bill could undoubtedly be made a lot more beautiful with some tweaks; ideally, fairly major ones. But it sure is big; and so, too, might be its impact.

Like a Rolling Stone

For years, now,

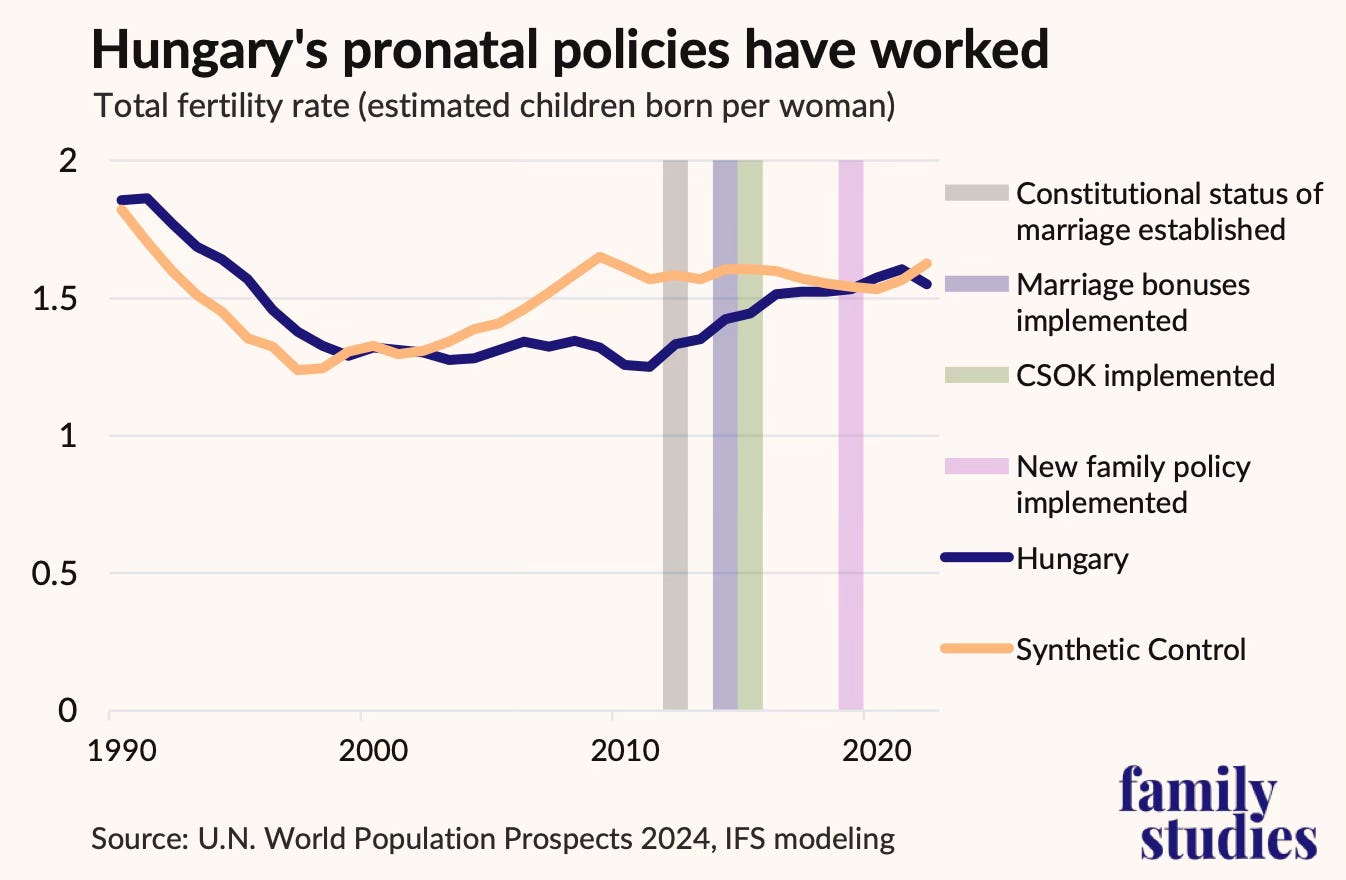

has been telling everyone that will listen that it’s not that pro-natal policy doesn’t work; it’s that it’s very expensive. His new report looks particularly at the example of Hungary (which devoted Family Matters will remember from a prior installment,) and argues that the country’s pro-natal policies “have worked.” I think that is true, in the sense that the country has pulled out of a tailspin — including, as previously discussed, performed the extraordinary feat of reversing the countries rise in the share of births out of wedlock. Of course, as Stone’s chart suggests, Hungary is notorious more for the rhetoric around its pro-family spending rather than anything particularly unique.4What’s less clear is whether the nation would consider the policies a success on their own terms and whether the recent bump can be sustained (i.e., pulling births forward isn’t nothing, but it’s also not the whole ballgame.) He argues that “even when tempo effects do make up a large share of the increased births from pronatal policies, that isn’t a reason not to pursue pronatal incentives...tempo effects are real demographic victories.” An important point, and one I agree with — but perhaps a less unconvincing point to the skeptics who wants to see proof that pro-natal policies can induce additional births, rather than simply speeding up ones that would have happened already. More rhetorical work in this space needs to be done.

Of particular note for our U.S. audience, he estimates a $1,000-per-year bump to the child tax credit could lead to an increase of births on the order of .05 births per woman, or about 2-5 percent (I’d suspect the true value would be on the lower end of that estimate given that our CTC is less generous to those who might expect to have a higher response to financial incentives.) Stone’s full report is at IFS.

It’s Me, Hi

I spoke to the The Dispatch’s morning newsletter, written by Charles Hilu and Peter Gattuso, about the priorities included in the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill,” including the point (familiar to Family Matters readers), that provisions like “No Tax on Tips” soaks up room that could be devoted to something like a “baby bonus”:

“It’s closer to a hybrid of traditional Republican approaches to some of this stuff with a dose of some, sort of, characteristic Trumpy populist stuff…Giving somebody a little bit of a nest egg and locking it up until they turn 18 doesn’t actually do anything to help parents who are trying to put food on the table that day or that week or that month.”

I also spoke to Rachel Cohen of Vox about the legislation that would require insurers to cover the costs of childbirth with no co-pays, co-insurance, or the like, the subject of last week’s Family Matters:

Patrick Brown, a family policy analyst at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center tells me he thinks it’s “the right instinct” to share the costs of parenting more broadly across society, though he hopes it does not “distract from more broad-based efforts to help parents” such as a larger Child Tax Credit.

Parting Shots

EPPC is hiring a full-time development assistant; the ideal candidate is a young professional interested in working in D.C. and with an interest in strengthening our mission by supporting our fundraising efforts. Apply here.

Ohio lawmakers are seeking to use the period between Mother’s Day and Father’s Day to pay tribute to the “natural family,” inspiring predictable cries of discrimination (NY Post)

Republican support for same-sex marriage continues to fall, dropping to 41% in Gallup’s latest poll on the issue (as recently as 2022, it was at 55% among Republicans). Interestingly, there isn’t a racial gap, but there is an education one (22% of college grads oppose same-sex marriage, while 34% of high school graduates do the same.)

An Ohio state house committee voted to advance a plan that would share the cost of child among parents (who would cover 40% of the cost of care), their employers (40%), and the state (the remaining 20%), a la the 'Tri-Care' program from that state up north - it would also prohbit the state regulator from requiring providers from participating in the state's quality improvement program to be eligible (Cleveland Plain Dealer)

A bill in the Texas legislature would require child care providers to report their openings to a state database, with the goal of helping parents more information about the child care market in the state (HB 2271)

Brad Wilcox encourages Ohio lawmakers to help “set young Ohioans up for success by providing clear teaching for our children on how education, work, and marriage are tied to greater financial security, emotional well-being, and family stability as they move through adolescence into adulthood.” (Family Studies)

Robert VerBruggen judiciously points out some of the flaws in the ‘One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act’ (City Journal)

After four years of giving cash to mothers below the poverty line, a team of researchers has found no discernible impact on the child's outcomes (NBER working paper 33844)

Republicans have much better ideas in their arsenal to help families than ‘Trump accounts,’ writes

(Bloomberg, but if you’re paywalled, her eponymous Substack)“Congressional Republicans are right that Medicaid growth is contributing to persistent annual deficits, and that entitlement reform more generally is essential for a return to fiscal stability. But from that sound starting position they are steering a course that will be hard to defend,” writes

for The Dispatch

Comments and criticism both welcome, albeit not quite equally; send me a postcard, drop me a line, and then sign up for more content and analysis from EPPC scholars.

Sen. Cruz is also behind another educational choice provision in the bill, expanding 529 savings accounts to be used for K-12 non-tuition expenses, including homeschooling expenses. He led the initial push to include K-12 tuition as a 529-allowable expense in 2017, which initially included homeschooling expenses but was stripped out to comply with the Byrd rule; the same fate might await this year’s amendment.

Interestingly, while the bulk of the expense would be borne by the federal government, the left-leaning Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy estimates that it could reduce state revenues by $2.3 billion over ten years due to the incentives to donate stock and thereby avoid paying state capital gains tax.

Recall that the House-passed bill only expands the top-line value of the CTC, not the refundable portion; so families with one earner below the median individual income and more than one kid may not see much benefit, if at all, barring other changes.

You should always be skeptical of synthetic control groups, particularly when they are picking up a lot more noise than the single intervention you’re trying to study, but in this case his construction shows that other countries were also adopting pro-natal policies, in some cases quicker and more effectively than Hungary.

School choice only works if private schools have the must accept public schools where those private schools can dump their problem children. And if demand for private schools increase, then more schools will be picking their students rather than student's families picking a school.