Breaking News: Divorce Is Bad for Kids

Pro-family initiatives should include building up societal connective tissue to reduce risk of divorce

Sorry, but we’re not done Pope Leo XIV-posting:

“It is the responsibility of government leaders to work to build harmonious and peaceful civil societies. This can be achieved above all by investing in the family, founded upon the stable union between a man and a woman, ‘a small but genuine society, and prior to all civil society.’ In addition, no one is exempted from striving to ensure respect for the dignity of every person, especially the most frail and vulnerable, from the unborn to the elderly, from the sick to the unemployed, citizens and immigrants alike.”

Now, back to business. If it’s Friday, it’s Family Matters.

Love on the Rocks: New research on the long-term harms of divorce

It’s Me, Hi: Commonplace, National Review, IFS, Deseret News, The New Populist

Parting Shots

Love on the Rocks

In American history, divorce gradually rose during the first half the twentieth century (with a large post-WWII spike; not all the marriages to returning GIs lasted). But with the arrival of no-fault divorce (the first such law, of course, signed in 1969 by California Gov. Ronald Reagan), divorce rates exploded, rising from a rate of 9.2 divorces per 1,000 married women in 1960 to 22 per 1,000 twenty years later.

The no-fault revolution is over. Part of this is mechanical, due to lower and later rates of marriage; people who don’t get married, by definition, can’t get divorced, and a couple that gets married at age 40 has less time for something to go catastrophically wrong than one who gets married at age 22. In 2022, women's divorce rate was 14.6, essentially back to where they stood in the early 1970s. But a new NBER working paper should push us to invest more time and resources into helping marriages stay strong. This isn’t (just) because conservatives have long believed that families are strongest, and thus their constituent members better off, when marriage is oriented towards fidelity and permanence. But the data continues to back this intuition up — most recently, in a direct reduction in the social and economic outcomes of children raised by parents who divorce.

The paper, by UT-Austin’s Andrew Johnston, Maryland’s Nolan Pope, and Maggie Jones at the Census Bureau links tax and Census data for all children born in the U.S. between 1988 and 1993 (how do you do, fellow end-of-history millennials?) Any time you can loop in Census data to your research idea, you’re cooking with gas, and this paper doesn’t fail to deliver.

A big debate in the literature around marriage and family always revolves around selection effects — for example, are people happier because they get married, or are happier people more likely to get married? For kids, it's even trickier - does the apparent negative outcomes associated with divorce caused by the dissolution of their parents marriage, or were the background factors that led to the divorce (unemployment, abuse, infidelity, et cetera) a bigger contributor to the negative outcomes we see?

The Johnston-Pope-Jones paper uses the universe of Census data to compare what happens when divorce happens at different points of a child’s life, rather than directly comparing children of divorce to children whose parents stayed together.1 By comparing siblings from the same family who were different ages when their parents divorced, they can control for a lot (though not all) of the factors that might create concerns about comparing apples to oranges. In so doing, they find that “divorce represents a significant turning point in children’s outcomes, and our sibling comparisons show that longer exposure to divorce has a lasting impact into adulthood.”

When parents divorce, for example, the average divorced household slips from the 57th income percentile to the 36th — by itself, a significant drop — their probability of moving triples, and they are more likely to move to neighborhoods that (if you believe Raj Chetty’s research, like you should) offer fewer pathways to middle-class economic opportunity. Half of parents remarry within the five years following the divorce, adding stepparents and the at-times messy relationships that can go with blending families.

In other words, as the authors write, “Children face not only changes in their family structure, but also widespread disruption to their material and social environments.” The three material channels the authors highlight are “changes in family resources, neighborhood quality, and parent proximity,” which of course says nothing about the fracturing of relationships or other non-quantifiable downstream consequences from divorce.

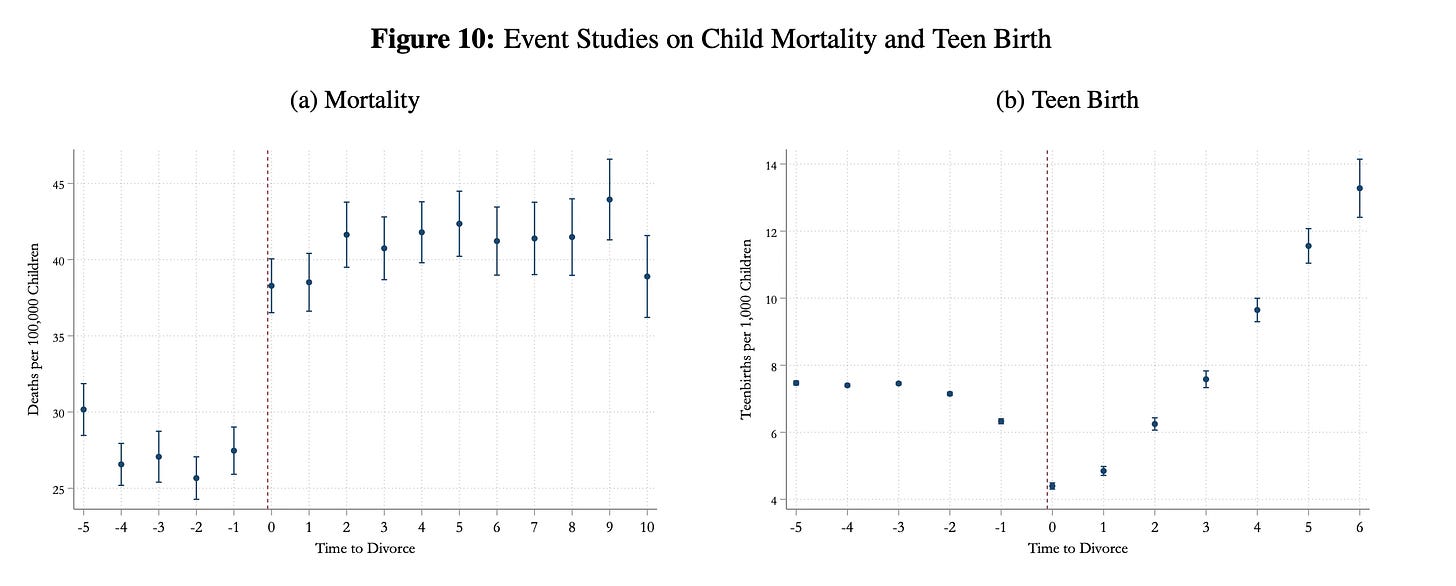

And as they take some pains to demonstrate, these effects seem driven by the divorce itself, since they find no pre-trends that could suggest a meaningful effect of deteriorating family environment prior to dissolution. The observed effect of a divorce on children is to raise their risk of death by 35 to 55 percent, and increase their odds of teen pregnancy by almost two-thirds. Children who are younger when their parents divorce have substantially lower incomes compared to those whose parents divorced after the children have left the home. They are less likely to attend a residential college and are more likely to be incarcerated.

Painting with a broad brush, it appears that children of divorce may have some advantages relative to those children whose parents never married, but fall well behind those whose parents stuck together. For instance, children of divorce have incarceration rates that are three times higher than children of always-married parents, but three times lower than the rate of children whose parents were unmarried. Their median income falls roughly halfway between the other family types as well.

The paper isn’t iron-clad; the authors do their best to account for reverse causality or endogeny of birth timing but naysayers will pick around the edges.2 But it should — as our friends on the left say — start a conversation about divorce in America, and increase efforts to help couples work through their difficulties and stay together.

Divorce has faded out of the spotlight somewhat, as lower marriage rates and greater selectivity into marriage means that divorce rates are well below where they were in the 1970s and 1980s.3 As a result, the share of kids living with divorced parents may well have peaked in the late 1990s. And it is difficult to talk about divorce, much less propose policy solutions about it, because no one wants to blame the victim (and most discussions of the topic carry a very understandable there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I energy, for obvious reasons). Virtually everyone alive can think of situations in which it was better for the parents to live apart rather than try to force an abusive, dangerous, or harmful situation to work for the sake of the kids. But the narrative around divorce as self-actualization (see

’s recent Substack on the memoirs from members of the “Hot Divorcées Club!” and Hulu’s new “Dying for Sex” miniseries) continues to chug along.The NBER authors cite a recent survey that found “divorced individuals cited relationship-focused reasons as primary precursors to divorce: ‘lack of interest in one another’ (48%), ‘poor conflict resolution’ (47%), and ‘avoiding one another’ (45%).” Only a small fraction cite abuse.4 More programming, investment, and just cultural openness to helping couples resolve those problems seem like a worthwhile initiative — both of the adults’ sake, and especially for any kids involved.

There may be larger cultural trends at play as well. In 2019’s Primal Screams, Mary Eberstadt offered an interpretation of the rise in identity politics as based in the breakdown of the family (reviewed for Claremont Review of Books by

, for the Washington Free Beacon by , and for National Review by .) “Our macropolitics have become a mania about identity,” writes Eberstadt, “because our micropolitics are no longer familial.” She pinpoints the dissolution of the traditional biological family, as we shifted away from an ideal of something oriented towards permanence to something contingent, comprised of no-fault divorce, anonymous sperm donation, missing family trees, and more. You don’t have to take Eberstadt’s thesis all the way5 to suggest that this is a massive shift, sociologically speaking, and that some of the dislocation felt in our culture’s unhealthy approach to politics and a hollowness at the heart of consumierism may be grounded in the loss of these traditional roots and belonging.Rebuilding a cultural understanding of marriage oriented towards permanence and fidelity is a long-haul battle. But — as with sports betting, and marijuana legalization, and scaling back crime enforcement, and gender transition surgeries for minors, and any number of progressive ideological trends which have been indulged over recent years that have not delivered the utopian vision once promised — social conservatives can claim at least some grim vindication, even if the human toll is unacceptably high. Fully recapture the pre-1969 world in which there was a broad, shared cultural sense that any divorce was a last-resort tragedy is likely impossible. But a cultural Marshall Plan aimed at building up social connective tissue that can help couples work through some of the most common problems that lead to divorce seems ripe for greater philanthropic, religious, and maybe even political efforts.6

It’s Me, Hi

We’ve had a busy week over here at Family Matters headquarters, so make sure to like and subscribe.

For Deseret News, I used the Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson bestseller (!) “Abundance” as a springboard to explore how, and how not, to think about reforming the child care market at the state level:

“An “abundance” approach to family policy should seek to expand the options that parents can choose between. In some cases, that could even look like a capacity expansion grant, where state money goes to childcare providers looking to expand or retrofit their space to serve more children. Using that framework requires us to be smart about identifying where bottlenecks exist and trying to address them, rather than ripping up the rule book and trusting the market will sort it all out.”

For Commonplace, I tweaked progressives who think that prioritizing families’ needs in transportation is “discrimination,” and offered some suggestions for a pro-family transit agenda:

“It wouldn’t take a revolution for policymakers to prioritize making our airports and highways more family friendly or pass symbolic steps to ensure families are recognized for their important work of raising the next generation.”

Online at National Review, I praised the good and questioned some of the flaws in the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” currently wending its way through the House:

“Overall, the legislation has something for everyone. But the amalgamation of tax policies, ranging from the expensive to the gimmicky, leaves Republicans facing a tightrope walk to secure passage. And it all adds up. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the package, as it stands, will increase the federal deficit by $3.8 trillion over ten years. This is a far cry from fiscal responsibility.”

And for Family Studies, I teamed up with

to argue that the “MAGA accounts” in the tax bill may be well-intentioned but won’t actually help parents when they need it most:“The “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” does best when it empowers families to do their best for their children, as with the CTC provisions that directly impact parents’ pocketbooks. The MAGA accounts, however, are something closer to a gimmick—neither calibrated toward parents’ needs nor likely to engender respect for their sacrifices.”

I spoke to MarketWatch’s Venessa Wong about the inclusion of said “MAGA accounts” in the tax bill, and why they’re not actually that family-friendly:

“That’s not the same as a tax code focused on improving the daily lives of American parents, whose worries about the cost of diapers and childcare and groceries are seen in our falling fertility rates.”

I spoke to Amanda Friedman at Politico about DOGE's cuts to the CDC's Division of Reproductive Health, and why taking a chainsaw to public health employees isn't always going to lead to better long-term outcomes:

“This is the kind of basic statistics gathering that there’s just not really a good free market solution for…Collecting data like this is a pretty classic function of government and it’s not something that you can rely on private industry or even academic institutions to do in the same scope or scale.”

I spoke to Elisha Brown of the States Newsroom about efforts to improve maternal health and invest in healthy babies and strong families:

“Oftentimes around childbirth, needs go up and income goes down. If we want to stabilize new parents, and we know that having resources is linked to better outcomes for mom and baby just because you can afford not to have to go back to work and all the rest, this is a way of recognizing that without having to build a huge paid leave entitlement.”

And, lastly, I did an interview with Lily Forand of

, a progressive outlet trying to find common ground between young populists on the left and right, over whether pro-family policies might garner bipartisan support:Parting Shots

Rep. Blake Moore (R-Utah) wrote last week that the Child Tax Credit “must be increased to $2,500 and tied to inflation.” He might get his wish! (Deseret News)

I expect isn’t the only libertarian-minded thinker who initially supported legalized sports betting and is now recognizing the growing downsides (The Dispatch)

Kathryn Jean Lopez, a stalwart on the pro-life beat, has started her own newsletter, The Lifeline, at National Review. Subscribe here.

Caroline Kitchener ably describes some of the intra-right contours around tax policy, child care, and stay-at-home parents — though I would push back against the description of the conservative vision of family policy as wanting couples to have "as many children as possible"! (New York Times)

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), quoted in Kitchener’s piece about pro-family policy, also wrote an op-ed for the Times making the political and moral case against relying on Medicaid cuts to balance the books for the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill.” In addition to proposed Medicaid cuts, Tony Romm reports on the potential impact of work requirements that would apply to SNAP (formerly known as food stamp) recipients up to age 64, including those with children as young as seven years old (New York Times)

- writes perceptively about the varying strains within the movement that is broadly in favor of having more children in the world, whether or not we call ourselves pro-natalists (I do not). (Law & Liberty)

A major research initiative into strengthening families is looking to hire an associate director. The ideal candidate would be based in the Midwest, with experience in operations, research, and policy. Contact me to be put in touch.

This is a very solid piece by

for her Substack , taking a comparative look at rates of part-time work among moms. One thing I would like to dig into is to what degree U.S. labor law incentivizes most firms to prefer an all-or-nothing model of labor force participation.

Comments and criticism both welcome, albeit not quite equally; send me a postcard, drop me a line, and then sign up for more content and analysis from EPPC scholars.

In so doing, they build on other research that leveraged quasi-experimental evidence suggesting divorce is bad for kids’ outcomes, most notably “Is Making Divorce Easier Bad for Children? The Long‐Run Implications of Unilateral Divorce” by Jonathan Gruber (JLE 2004). On a shorter-term time horizon, a team out of Denmark found divorce caused a drop in kids’ test scores.

To translate that, some might worry that negative circumstances around the birth of a child could lead to a divorce, rather than the child’s negative outcomes being caused by the divorce, or that the timing of a formal divorce might be sufficiently different from the breakup of a household to render their study unreliable. An initial eyeball test suggests those concerns aren’t serious enough to undermine the paper, but reviewers will assuredly be digging in.

If you hear someone repeating the FAKE statistic that “one in every two marriages today end in divorce,” report them to the authorities for abetting the spread of disinformation.

My more, er, redpilled friends like to cite the finding that “women initiate 70 percent of divorces;” but that only speaks to the precipitation of the breakup, not whatever causes (infidelity, lack of communication, disinterest in fixing the relationship, etc.) undergird the ultimate decision.

For instance, I think the point Sibarium makes in his review - that the rise in ideological progressivism has been most heavily concentrated in white, college-educated Americans, whose families have been rocked less by dissolution and breakdown than non-college or minority Americans - complicates her story about the political ramifications of family alienation.