A Full Dinner Bucket

Deliberately reducing household purchasing power won't make families great again

Hello, friends. If it’s Friday, it’s Family Matters:

The Main Event: Weighing Tariffs

DOGE Day Afternoon: Measure Once, Cut Twice

It’s Me, Hi: EWTN News

Parting Shots

The Main Event

The steelman case for pro-worker conservatives looking at the last two weeks of trade policy goes something like this:

“Well, no, the rollout wasn’t smooth, but directionally, the White House is correct to try to fundamentally restructure the terms of global trade. The golden age of the American middle class was built on a stable manufacturing base, and heavy tariffs will reward firms for relocating their assembly lines stateside. Dedollarization will lead to a weaker dollar, boosting demand for U.S. exports and raising working-class wages. Plus, the jobs created will skew towards blue-collar males, and boosting their economic prospects will help rebuild a strong marriage culture and rejuvenate boarded-up Rust Belt towns. We can all agree the implementation and messaging needed work, but the goal set forth on Liberation Day is long overdue.”

It’s an attractive story, but it lets the actual policy design off the hook. Targeting the U.S.’ trade deficit with each individual nation would directly reduce American families’ purchasing power without anything close to commensurate benefit to domestic producers. The approach that was outlined on April 2 amounted to staking the fate of the U.S. economy to a gamble that will not deliver on its promises, due to structural factors that no executive order can do anything about.

Yes, on Wednesday the President announced a 90 day “pause” on the reciprocal tariffs.1 The rush to negotiate various deals and accords to soften the impact of the planned tariffs begins in earnest. But it wasn’t just the implementation that was bad; the posterboard framework laid out on Liberation Day was wrong. Taking the pro-labor case for tariffs seriously can help us see why.

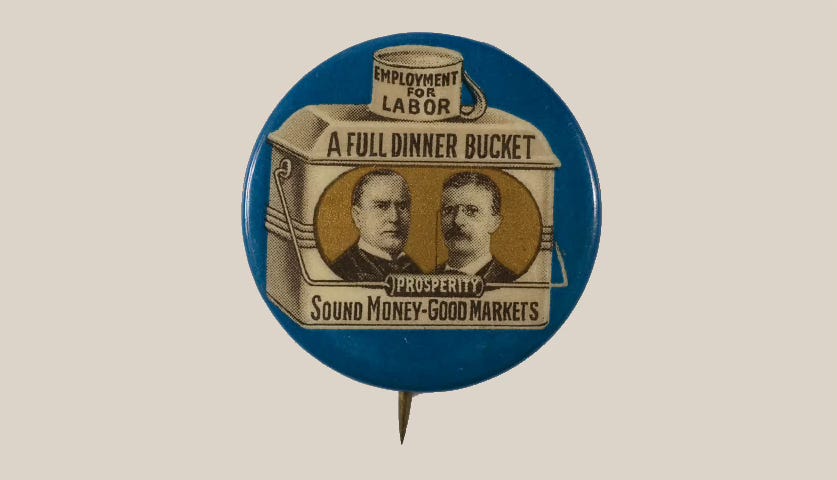

Some arguments in favor of reciprocal tariffs are easily dispensed with. Yes, it’s true that in the McKinley era — when he and TR ran on the slogan that pro-labor Republicans would ensure “a full dinner bucket” for workers — tariffs produced the bulk of federal revenue; but it’s also true that the federal government did a lot less then (think Medicare and the military, not the Department of Education).2 Yes, some countries — starting with, but not exclusive to, China — have been bad actors in the global marketplace; but no, cracking down on bad apples doesn’t justify tariffing the penguins of Heard and MacDonald Islands. Yes, too many companies have allowed short-term profits to lead them to cozy up to authoritarian regimes and turn a blind eye to human rights violations; but the answer to that is to encourage the continued shift of supply chains to other low-cost countries with better protections for labor and relationships with the U.S., like Vietnam, not to slap a punitive, 46 percent “reciprocal” rate on a key trading partner.

But the deeper argument, that we need these tariffs to restore American industry and support good jobs, deserves to be grappled with. It’s the old tradeoff from protectionist voices — everyone should pay a little more upfront in order to buttress the wages of workers on the line.3 As a political gambit in 2025, it’s a relatively high-risk one — acutely aware of the pain of living through the highest inflation in 40 years, Americans elected Donald Trump in large part to bring prices down. In response, the White House is choosing to implement tariffs, which will send prices up, in hopes of rebuilding domestic supply chains and manufacturing jobs stateside over the long run.

Take, for example, the vision of Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick — “the army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little, little screws to make iPhones, that kind of thing is going to come to America.” According to the Wall Street Journal, assembly costs for the latest iPhone would increase roughly tenfold, from $30 to $300, if moved from China to the U.S., which could theoretically boost domestic wages. But given our relatively tight labor markets and demographic headwinds, it’s not prima facie evident that shifting workers from one sector to phone assembly is the ticket to sustainable wage growth. As

’s pointed out last year, the meme of stagnant wages for low-wage workers is disproven by two periods of sustained growth — the late 90s, and the ongoing rise from the middle-2010s. Re-shoring low-skill assembly line work simply isn’t necessary to drive strong wage growth at the bottom of the income distribution — and could even undermine that goal if it led to a wage-price spiral.But let’s, for the sake of argument, assume that reshoring production domestically is desirable, and that we could reorient our labor force and educational training efforts to provide blue-collar workers in the quantities such efforts would require. The inherent trade-off is still there — most Americans would be paying more at the register in order to protect the domestic manufacturing jobs created by these new trade barriers. Sure, you can (and should?) survive without buying the latest iPhone. Seniors who live off a fixed income would obviously feel the pinch of higher inflation.

But so, too, would budget-conscious families who tend to consume a higher proportion of foreign-made consumables. Strollers and carseats are predominantly produced abroad, meaning today’s parents would pay higher amounts out of pocket until a manufacturer had the confidence and ability to bring a U.S. plant online. Electronics, toys, sporting equipment, and furniture are some of the goods that are most likely to be hit by this approach — without an alternative plan, kids clothes, shoes, baby bottles, and the like will all either see a price increase due to the increased tariff or switch to a more-expensive alternative. An sudden imposition of heavy tariffs is a direct reduction in families’ ability to purchase these goods.

Additionally, the blinkered focus on each individual country’s trade deficit with the U.S. necessitates tariffs on coffee, vanilla, bananas or other household staples for which there is no meaningful domestic equivalent, reducing families’ standard of living without any commensurate benefit. As Alan Cole pointed out for The Dispatch, there is no world in which Madagascar, a key source of imported vanilla, will have the wherewithal or need to buy high-value manufactured goods or financial services from U.S. firms. Levying high duties on imported vanilla isn’t going to help the bespoke vanilla farms in Hawaii grow enough to meet domestic demand, and thereby reduces any given family’s ability to bake chocolate chip cookies. Repeat at larger scales, and the downside economic and political risk of high tariffs becomes too visible for anyone to ignore.

Everyone who is not already pre-committed will admit the implementation of the tariffs had significant flaws. Even before the pause was announced, , one of the biggest intellectual influences on the pro-tariff side, had offered his recommendations for how the administration could “correct course and move from its embattled beachhead into a sustainable forward position,” steps the administration seemed to take to heart. The messaging from corners of the MAGAverse, too, could use some work — the number of conservative influencers who made some version of the argument that money isn’t real or no one checks their retirement accounts has been a degrowther’s dream. But some may still argue that, done right4, the kind of heavy-handed tariffs aimed at leveling bilateral trade deficits rolled out by the White House on Liberation Day remain the right way to go about the goal of a stable blue-collar middle class.

Yet the Liberation Day approach can’t be fixed by just doing it more gradually. Economists have long pointed out the hidden costs to each job created or preserved by policies like tariffs. In the textbook model, tariffs, like any other tax, lead to deadweight loss. As opposed to a tax on earnings or a tax on consumption, a tax on inputs distorts investment decisions, and the regulatory uncertainty and special-interest pleading directs capital investment to less-productive ends. There are times when those costs are worth bearing — decoupling from China being a laudable goal, worth the economic pain (though an effective immediate embargo may create more pain than is strictly necessary). But applying the same broad brush stroke to partners like Israel, the UK, or Australia, particularly with a reliance on Presidential-level idiosyncratic bargaining, makes it harder for American business to predictably invest over the long run.

And more fundamentally, a McKinley-ite view of tariffs as prioritizing producers over consumers may have been the right ticket when the U.S. was a nation embarking on its path towards industrialization, rather than one that has been increasingly post-industrial not since the China Shock, nor NAFTA, but since the 1970s, when each subsequent recession ratcheted our share of the labor force working in manufacturing downwards and the global economy became more interconnected.5

In the late 1990s, policymakers from both parties mistakenly assumed that granting China permanent most favored nation status would help the Middle Kingdom towards liberalism and democracy. This was wrong and had especially painful consequences for certain manufacturing-heavy regions of the United States. Strategic rearmament of America’s manufacturing base, particularly its advanced, high value-added sectors, is a necessary and laudable policy goal (typified by the energy behind the CHIPS bill, if not its everything-bagel implementation.) As of Apricitas Economics never fails to point out, computer and electronic manufacturing now makes up more than half of U.S. manufacturing construction — industrial policy at work.

But this good and necessary policy push is going to more often look like a highly-automated clean room than the lunch pail assembly lines of the 1960s. Even the near-impossible task of doubling the number of Americans working in manufacturing (currently 12.7 million) would place the share of the labor force working in those merely at the level it was in the mid-1980s, at which point the transition away from a manufacturing-oriented economy was already well underway (“My Hometown” was released in 1984!) America’s heavily services-based, post-industrial economy isn’t going to outcompete Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia, or India in being able to throw large numbers of relatively unskilled workers at producing low-cost consumer goods.

Seeking to eliminate our trade deficit with nations with a low standard of living and lots of workers working low-wage manufacturing jobs is, quite simply, the wrong policy goal. Reshoring sneaker production in the United States would push prices up without providing something tight labor markets can’t provide themselves. If, after the chaos, we end up with one-time, permanent, 10% universal tariff (like that proposed by Cass), it will, to its credit, be far less distortive and easier for firms (and foreign allies) to adjust to relative to the Liberation Day posterboards. It will still likely raise prices and ding American producers who rely on foreign inputs (that is to say, nearly all of them). And it will still be increasing frictions that are not necessary to achieve our goal of delivering wage growth to workers and affordable standards of living to families.

Economists have long known that “technological change creates winners and losers and can sometimes have adverse distributional consequences that may foment social tension.” The American economy of the 1950s and 1960s was one in which most European nations were focused on internal rebuilding after wartime devastation, the Soviet bloc was closed to us, and most of Asia and Africa was still considered the Third World. None of that is true today. The integration of the global economy and technological advances means that anyone who hears that tariffs will restore a Golden Age of American manufacturing is being sold a bill of goods. The ultimate goal should be reorienting our economy to allow workers without a college degree to be better providers for their families — that starts with tight labor markets, a stable regulatory environment, and recognizing that today’s economy is going to provide stability for workers in different ways than the Fordist economy of yesteryear.

So long as the American economy can continue to drive wage growth for the average worker, it can provide the engine for widespread prosperity, especially with appropriate supply-side reforms. That’s going to mean something different than the Springsteenian romance of the assembly line. Place-based policy can play a role; more non-college tracks in education and apprenticeships and even labor reforms can help as well. There are strategic investments and supply-side reforms that may well unleash an industrial boom without ad hoc tariff formulae that have the (un?)intended side effect of telling financial markets that the U.S. dollar is no longer a safe investment. But we have a model for what those kind of efforts can produce: 2018 and 2019, not 1954 or 1965.

And as we saw in 2008 (the start of the birth decline in America), widespread economic pain is the furthest thing from pro-family. Crashing the global economy with abrupt and too-heavy tariffs would have made it harder, not easier, for couples looking to buy a home. Additionally, as the work of Melissa Kearney and Riley Wilson shows, localized boosts in wages for male workers without a college degree did not lead to any perceptible increase in marriage rates during the shale boom; so the pro-marriage case for tariffs rest on a thin reed as well. Unleashing productive investment and empowering a 21st century housing boom would be the kind of liberation we’re looking for.

The Liberation Day approach cost the administration credibility and threatened that broader agenda. The goal of eliminating all bilateral trade deficits was the wrong one, implemented shambolically. Perhaps the 90-day pause will end up producing an equilibrium outcome of a high tariff on China and a flat (and stable!) universal tariff elsewhere; much better compared to many of the alternatives. But if we care about families’ well-being, the “full dinner bucket” of today is one that relies on an affordable standard of living (which is why we need to build more, and faster, not slap tariffs on Canadian hardwood!) and healthy, stable labor markets. For those on the right, the goal is how to best to fill up that bucket without relying on explicit income redistribution between earners — whether that hesitation should extend to households with dependents (that is, children) is a live and ongoing debate...a topic for another day.

DOGE Day Afternoon

The DOGE impulse to cut anything that looks “non-essential” has been previously criticized in the august pages of Family Matters. It struck again, cleaving deep at HHS, with a number of high-profile slashes that should concern conservatives. As Alanna Vagianos of HuffPo reported, the DOGEification of HHS wiped out “the majority” of the CDC's Division of Reproductive Health, the group that tracked both IVF statistics and maternal and infant health outcomes.

I have little doubt that I would run the CDC differently than past directors, and the new leadership may indeed steer the department in new and healthier directions. However, refusing to collect or publish regular surveillance data is needlessly hamstringing the public good function of a department of health. It does us little good to have to rely on counts from vested interests, like WeCount or the Guttmacher Institute, rather than have the CDC’s annual data showing the number of abortions nationwide. As an unnamed researcher quoted by Vagianos says about IVF records, “Where there’s profit, there’s a need for transparency and independent data.” That need will only grow if the White House acts on its stated intention to expand access to IVF.

, formerly of HuffPo and now at

, estimated that 40 percent of the staff of the Administration for Children and Families, the wing of HHS responsible for federal child care programs, marriage promotion efforts, etc., had also been abruptly let go. The division focused on reducing rates of domestic violence was likewise disbanded. The reduction in force orders also reportedly eliminated the Division of Data and Technical Analysis, which had responsibility for adjusting the federal poverty line.There may well be plenty of fat to trim in the public health bureaucracy. But these kind of abrupt, indiscriminate cuts — even if they don’t raise an immediate political risk — aren’t going to make it easier to raise a family in America, particularly for those who are just barely making ends meet.

It’s Me, Hi

I and some friends made cameos in ETWN News Nightly’s coverage of the recent Danube Institute conference on “Family Formation and the Future”:

Solène Tadié also covered the panel, featuring Brad Littlejohn, Tim Carney, Fiona Bruce, and yours truly, for Catholic News Agency:

“Society relies on the contributions of parents,” Brown noted. “Parents are bearing the cost of raising kids individually, but the benefits flow to the rest of society.”

Parting Shots

Upcoming Event: The Niskanen Center will be holding an event on The Earned Income Tax Credit at 50 on April 23 at 12p at the Senate Visitor Center. Panelists include Margot Crandal-Hollick, Emily Wielk, Nina Olson, and Josh McCabe. RSVP here.

If Congress was interested in swinging big, in a fiscally sustainable manner, they could do much worse than to read Margot Crandall-Hollick’s report on improving low-wage and child credits in the tax code (Tax Policy Center)

Brian Faler writes about the efforts to expand the Child Tax Credit in Congress, though I’d take some issue with the framing — the CTC, far from being an exclusively Democratic calling-card, was first passed by a Republican Congress in 1997, then expanded with a GOP Congress and White House in 2001, 2003, and 2017. (Politico)

Working parents who take parental leave and then opt not to return to work would be protected from having their benefits clawed back under a new bill from Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Rep. Riley Moore (R-W.V.) It's a fairly narrow issue, but seems like a matter of fairness.

Democratic Senators, led by Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.), introduced their updated child tax credit bill, seeking to restore the Biden-era universal Child Tax Credit, and also index it to inflation and provide up-front assistance as soon as a new baby is born

Charlie Camosy argues that post-Dobbs, pro-life laws have protected thousads of unborn children, abortions have increased, and the pro-life continues to face significant messaging (and, I'd add, strategic) challenges (First Things)

Ramesh Ponnuru points out that despite libertarians' worst fears, tax benefits for families in the tax code routinely lose their real value and are overdue for an update (Washington Post)

, , and Elise Anderson offer some suggestions about how to reform the Child and Dependent Tax Credit to be provide more egalitarian support families (Capita); also at Capita,

, , and Caroline Cassidy offer “common good pluralism” as a way of thinking about how to make society “better, not just richer.” Much to chew over.Anna Louie Sussman finishes her three-part series on the biology and legal status of embryos for the New York Times (part one; part two)

correctly notes that declining fertility rates are being driven by declining marriage rates, not by increased educational attainment, though policy steps to make it easier for people, including those in grad schools, to start families earlier should be a point of bipartisan agreement:

Comments and criticism both welcome, albeit not quite equally; send me a postcard, drop me a line, and then sign up for more content and analysis from EPPC scholars.

Of course, the rates announced on April 2 were not actually reciprocal, in any meaningful sense, but simply calculated by dividing the US goods trade deficit by the value of goods imported from a given country, then dividing that figure by two. But that is what the agreed-upon nomenclature seems to be.

In the 1900s, the federal government outlays were about 3% of GDP, largely on the military and debt and pensions related to the Civil War; in the 2010s, it was been around or over 20% of GDP

See similar arguments in the recent longshoreman labor dispute, with some distinct parallels in some of the arguments for Biden’s “Inflation Reduction Act”

No small caveat, as the formula used by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative shows (Never go up against Kevin Corinth when elasticities are on the line.) Executive branch armchair social science hasn’t been this much fun since the days of the “cubic fit” model!

In the chart below, the blue dashed line represents when NAFTA took effect in Jan. 1994, and the red dashed line when China was granted permanent most favored nation status in Dec. 2001.

Yeah I fear that the admin has some true believers who don't have enough actual operating experience to know that manufacturing won't ever come back in its former way but will need reinventing and creativity, maybe even a millionfold increase in small shops for some goods. But I think also the true finance guys in the admin will just try to weaken the USD, slash spending, finally crack the Fed to lower rates, get a mild recession and leave at least baseline 10% tariffs in place, then declare victory and pass a big deregulation, infrastructure and pork bill.